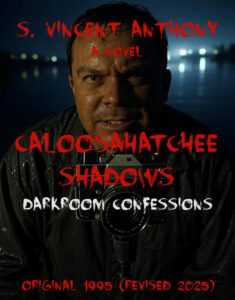

Written by S. Vincent Anthony

Original 1995 (Revised 2025)

Dedication: To the shadows that hide in plain sight, and the light that reveals them.

Prologue

Prologue

The humid night air of Cape Coral, Florida, in August 1995 wrapped around Julian Crane like a damp shroud, thick with the scent of mangrove mud and the faint tang of saltwater carried on the Gulf breeze. The city, a sprawling grid of over 400 miles of artificial canals—more than Venice, Italy—hummed with the low drone of air conditioners and the occasional splash of mullet breaking the surface of the Caloosahatchee River. Cape Coral, born from the ambitious dredging of swamps in the 1950s by the Gulf American Land Corporation, had grown from a notorious land scam into a booming haven of 80,000 residents, its pastel homes and palm-lined streets drawing retirees and young families to its promise of waterfront living. But beneath the sun-soaked facade, darker currents flowed—deals sealed in smoke-filled rooms, bodies lost in the labyrinthine waterways.

Julian stood on the polished teak deck of Shadow Play, the Crane family’s 60-foot Hatteras yacht, moored in a private slip behind their estate in the Yacht Club neighborhood. The vessel gleamed under the dock lights, its chrome fittings catching the scattered stars, its cabin windows dark but for the soft glow of a single brass lamp. At 29, Julian was a striking figure: tall and lean, with a sharp jawline inherited from his father and blue eyes that seemed to dissect the world into frames of light and shadow. Around his neck hung his Canon EOS-1, a professional 35mm SLR camera prized for its precision, loaded with Kodak T-Max 400 film, its fine grain ideal for the low light of dusk.

Richard Crane, 55, leaned against the yacht’s railing, a tumbler of Jack Daniel’s Single Barrel in his tanned hand, ice clinking softly as he swirled the amber liquid. His silver hair was slicked back, catching the light, and his linen shirt was unbuttoned at the collar, revealing a gold chain with a St. Christopher medal—a relic from his late wife, Elena. Richard’s presence dominated the space, like the plume of smoke curling from the Montecristo No. 2 cigar in his other hand, a habit from his youth in Tampa’s Ybor City. “Power is like your photography, son,” he said, his voice a gravelly baritone shaped by decades of commanding boardrooms and intimidating rivals. “You control the frame, the exposure. Let in too much light, and the image burns out. Too little, and it’s just a blur.”

Julian’s fingers grazed the camera’s shutter button, the leather strap worn smooth from years of use. “And the subjects, Dad? What if they don’t pose right?”

Richard’s chuckle was cold, like gravel shifting underfoot. “You make them. Or you crop them out.” His dark eyes, shadowed by heavy brows, flicked to the river, where a faint splash—perhaps an alligator—rippled the surface. “You understand that, don’t you?”

Julian nodded, his pulse steady but his mind alight with anticipation. He raised the camera, framing his father against the twinkling lights of Fort Myers across the river, the city’s modest skyline a jagged silhouette against the indigo sky. The shutter clicked, the mechanical whir a satisfying punctuation. “One for the album,” he said, lowering the lens.

Richard took a sip of bourbon, the ice catching the light like tiny prisms. “We’ve got a problem brewing. That reporter, Lena Voss—she’s digging too deep into the marina project. Asking about permits, payoffs, the Trafficantes.”

Julian’s grip tightened on the camera. The Riverfront Marina, a $200 million development along the Caloosahatchee, was Crane Enterprises’ crown jewel, a sprawling complex of luxury condos, yacht slips, and retail that displaced low-income neighborhoods and razed mangrove forests. Lena’s articles in the Fort Myers News-Press had stirred whispers in Tallahassee, where Governor Lawton Chiles, fresh off his narrow 1994 victory over Jeb Bush, was pushing environmental reforms. Richard’s ties to the Trafficante crime family—Tampa’s Mafia legacy, weakened since Santo Trafficante Jr.’s death in 1987 but still potent in construction and gambling—ensured the project’s approval, but Lena was a threat.

“I’ll handle it,” Julian said, his voice calm, almost musical. Inside, a familiar thrill coiled like a spring. This wasn’t his first assignment, nor would it be his last. He’d been groomed for this—by Richard, by the shadows.

Richard exhaled a plume of cigar smoke that drifted toward the stars. “Good. Clean, like always. No loose ends.”

Julian retreated to his cabin below deck, where a portable darkroom was set up on a folding table—trays of developer and fixer, the vinegar tang of chemicals sharp in the confined space. He developed a test roll from earlier that day, images of a derelict shrimp boat in Matlacha, its hull rusted and barnacle-encrusted, tilted in the mud like a fallen giant. Under the red safelight, the prints emerged in the tray, their edges curling slightly. The interplay of decay and beauty was a metaphor for his work—both the art he showed the world and the darker craft he hid. He clipped the prints to a drying line, imagining Lena Voss as his next subject, her life reduced to a perfect, frozen frame.

Part I: The Frame

Chapter 1: Aperture of Control

The morning sun burned through the tinted floor-to-ceiling windows of Julian Crane’s penthouse studio in Harbor Towers, a 15-story high-rise that stood out like a glass monolith among Cape Coral’s low-slung homes. Built in 1987 during a brief skyscraper craze, the building offered sweeping views of the Caloosahatchee River, its waters glinting like molten silver under the August heat. Inside, the air conditioner hummed steadily, maintaining a crisp 68 degrees against the 95-degree swelter outside, where palm fronds drooped and the air shimmered with humidity. The 2,000-square-foot studio was minimalist: polished concrete floors, white walls hung with oversized black-and-white prints, a stainless-steel kitchen island where Julian now stood, sipping black coffee from a chipped ceramic mug etched with the logo of a Key West café. The bitter taste grounded him as he spread contact sheets across a light table, their tiny 35mm frames glowing under the fluorescent bulb.

Julian’s photography had earned him acclaim in the art world. His images captured Florida’s hidden scars—abandoned orange groves in Immokalee, where skeletal trees stood like ghosts under a merciless sun; derelict motels along U.S. 41, their neon signs faded to ghosts of the 1960s; the weathered faces of migrant workers picking fruit in the fields of Clewiston. Galleries in Miami’s Design District and New York’s SoHo praised his “raw authenticity,” unaware that his true masterpieces were never exhibited publicly. He worked exclusively with film, favoring Kodak Tri-X for its high contrast, developed in a custom darkroom at the back of the apartment. The room, sealed with blackout curtains, smelled of chemicals—developer, stop bath, fixer—a ritualistic perfume that steadied his nerves.

Born in 1966, Julian was the only child of Richard and Elena Crane, raised in a Cape Coral still shaking off its reputation as a 1950s land scam, when the Gulf American Corporation sold flooded lots to unsuspecting northerners, leading to lawsuits and state crackdowns. Elena, a Cuban refugee who fled Havana in 1960 after Castro’s rise, had been a photographer herself, snapping family moments with a Kodak Instamatic. She gave Julian his first camera at age 8, teaching him to frame the world through a viewfinder, her soft accent guiding him: “Find the story in the light, pequeño.” Her death in 1976, officially a boating accident during a Gulf storm, left a void. Julian, at 10, remembered her screams from the night before, Richard’s voice booming through the estate’s walls, the faint marks on her wrists she hid with long sleeves. He never asked; Richard’s silence was law.

The rotary phone on the kitchen island rang, its shrill bell cutting through the hum of the AC. Julian set down his mug, the coffee ring staining a contact sheet. “Crane,” he answered, his voice smooth, practiced.

“Mr. Crane, it’s Lena Voss from the Fort Myers News-Press.” Her tone was bright, eager, with a faint Southern lilt from her Fort Myers roots. “I saw your exhibit in Miami last month—those shots of the Everglades, the decay in paradise. Stunning. I’d love to interview you, maybe tie it to local development issues. Your father’s name comes up a lot.”

Julian’s lips curved into a smile she couldn’t see. “I’m flattered, Lena. Come by the studio tonight, 9 p.m. We’ll talk.”

“Perfect. See you then.”

He hung up, his mind already framing the evening. Lena Voss, 26, was a rising star at the News-Press, her investigative pieces on Cape Coral’s explosive growth stirring trouble. She’d uncovered emails—leaked by an anonymous whistleblower—suggesting Crane Enterprises bribed city council members to fast-track the Riverfront Marina, a $200 million project that displaced low-income neighborhoods and razed mangrove forests critical to the ecosystem. Worse, her latest articles hinted at ties to the Trafficante crime family, the Tampa-based Mafia that, though weakened since Santo Trafficante Jr.’s death in 1987, still controlled construction and gambling rackets in Southwest Florida.

Julian crossed to the darkroom, its door hidden behind a sliding panel painted to match the wall. Inside, under the red safelight, he prepared with surgical precision. From a locked cabinet, he retrieved a vial of midazolam, a sedative sourced from a Fort Myers pharmacist who owed Richard for a forgiven gambling debt. He’d tested it earlier that week on a stray cat near the canal behind the building, watching its eyes glaze over in minutes, its body limp in the sawgrass. Satisfied, he measured a dose into a syringe, then diluted it in a bottle of pinot noir, the crimson liquid swirling like blood in the dim light.

He set up the studio: a velvet chaise longue, deep burgundy, positioned near the windows where the river’s dark flow reflected the city lights; Quartz halogen lamps on C-stands, their light softened by diffusion panels to mimic moonlight; his Canon EOS-1 on a Manfrotto tripod, loaded with Ilford HP5 film pushed to 1600 ASA for the dim interior. He tested the shutter, the motor drive whirring, each click a heartbeat.

At 9 p.m., a sharp knock echoed through the studio. Lena stood in the hallway, her red hair tied in a loose ponytail, freckles dusting her nose, green eyes bright with purpose. She wore a light cotton sundress, practical for the oppressive heat, and carried a spiral notebook and a Sony Walkman Professional tape recorder, its silver bulk clipped to her belt. “Thanks for seeing me, Mr. Crane,” she said, shaking his hand. Her grip was firm, confident, her skin cool despite the humidity outside.

“Call me Julian,” he replied, gesturing to the chaise. “Wine?”

They sat at the kitchen island, the river’s dark expanse visible through the windows, a distant boat’s wake rippling the surface. Lena set up her recorder, the red record light blinking like a warning. “Your photos strip Cape Coral bare,” she said, flipping open her notebook. “The flooded canals, the bulldozed mangroves, the forgotten people. It’s like you’re exposing what everyone else ignores. Does your father’s work with Crane Enterprises ever conflict with that vision?”

Julian poured the wine, handing her the spiked glass. “Art is about truth,” he said, sipping his own, untainted drink. “Business is about progress. They don’t always align, but I stay out of his deals.” He watched her drink, the liquid catching the light.

She nodded, scribbling notes in shorthand. “Your father’s marina project—it’s displacing families in the Northwest quadrant, destroying ecosystems. My sources say there’s dirty money involved, maybe even mob connections. Care to comment?”

Julian’s smile didn’t waver, a practiced mask honed over years of deflecting. “You’re direct. I like that. But I’m just an artist, Lena. I capture what I see, not what I hear.”

They talked for an hour—his influences (Ansel Adams for composition, Robert Frank for rawness), the grit of Florida’s underbelly, her passion for journalism rooted in watching her father, a shrimper, lose his livelihood to overdevelopment in the ‘80s. “The Gulf used to be alive,” she said, her voice softening. “Now it’s condos and oil slicks.” The sedative crept in; her words began to slur, her eyelids drooping like wilting hibiscus petals. “I feel… dizzy,” she murmured, her hand slipping from the notebook.

Julian caught her as she slumped, guiding her to the chaise with gentle precision. “Rest,” he said softly, his voice almost tender. He posed her meticulously: one arm draped over the edge, fingers curled slightly; her hair fanned out like a fiery halo across the velvet; her eyes, now glassy and unfocused, catching the soft glow of the lamps. “You’re beautiful like this,” he whispered, his breath quickening with the thrill. The camera’s motor drive whirred, capturing 36 frames—close-ups of her face, the delicate curve of her neck, wide shots of the scene, the interplay of light and shadow on her paling skin, the river’s reflection a ghostly backdrop.

At 1 a.m., he loaded her body into the trunk of his black Mercedes-Benz 500SL, a sleek convertible that purred through Cape Coral’s quiet streets, the top down to blend with the night traffic. The radio played Alan Jackson’s “Chattahoochee,” the twang of guitars mingling with the hum of tires on asphalt. He drove to a remote canal off Burnt Store Road, a desolate stretch where sawgrass swayed and alligators’ eyes glowed like embers in his headlights. Using cinder blocks from a nearby Crane construction site—ironically, part of the marina project—he weighted the body, watching it sink into the brackish water, bubbles rising like fleeting spirits in the moonlight.

Back in his darkroom, he developed the negatives under the red safelight, the chemical tang of fixer sharp in his nose. The prints emerged in the tray—Lena’s eyes staring eternally, her form a study in tragic beauty, the shadows pooling like ink. He titled the series Fleeting Shadows, destined for a black-market gallery in Miami’s Design District, where anonymous collectors paid exorbitant sums for pieces laced with unspoken danger.

As dawn broke, painting the river pink and gold, Julian’s pager buzzed—a Motorola StarTAC, cutting-edge for 1995. The message was from Sarah Kline, his gallery assistant in Miami: “Exhibit sold out. Dinner soon? – S.” He smiled, the thrill of the night still pulsing through his veins, but a flicker of emptiness stirred deep within, like a shadow moving across a negative.

Chapter 2: Shadows of the Past

Julian navigated his Mercedes along Cape Coral Parkway, the morning sun glinting off the canal bridges, each lined with royal palms bending in the humid breeze. The city’s grid was hypnotic—endless straight streets intersected by waterways, a planned community that felt both utopian and sterile, its 400 miles of canals a testament to human ambition over nature. The air was thick with the scent of cut grass and blooming oleander, the distant rumble of construction equipment signaling another Crane Enterprises development. He headed to the family estate in the Yacht Club neighborhood, a 10,000-square-foot Mediterranean villa built in 1972, its coral-colored stucco walls and red-tiled roof a monument to Richard Crane’s ambition. The estate sprawled across 10 acres, with manicured lawns dotted with coconut palms, a private dock extending into the Caloosahatchee, and an infinity pool that seemed to merge with the river’s shimmering surface.

Richard greeted him at the door, dressed in a cream linen suit, his St. Christopher medal glinting against his tanned chest. “You’re late,” he said, his voice a low growl, leading Julian to the study. The room was a fortress of power: mahogany walls lined with shelves of leather-bound law books, a Rolodex thick with contacts—politicians, developers, lieutenants of the Trafficante crime family. A framed map of Cape Coral’s canal system hung above the desk, its blue veins tracing the city’s engineered birth. A humidor of Cuban cigars sat beside a silver coffee urn, its aroma mingling with the faint musk of old books.

“Clean?” Richard asked, pouring coffee into Wedgwood cups, the porcelain clinking softly.

“Lena’s gone,” Julian replied, setting his camera bag on the desk, the Canon EOS-1 nestled inside. “No traces. Body’s in the canal, weighted. Photos are… exceptional.”

Richard nodded, but his dark eyes narrowed, assessing. “Good. But we’ve got eyes on us. That detective, Sam Carver—he’s sniffing around the News-Press, asking about Lena.”

Julian’s mind flashed back to 1976, a memory as vivid as a freshly developed print. He was 10, standing on the deck of Shadow Play during a Gulf storm, rain lashing his face, the wind howling like a banshee. His mother, Elena, had argued with Richard the night before, her voice shrill through the estate’s walls: “You’re a monster, Richard!” A glass had shattered, followed by silence. The next day, Elena went boating alone—or so the official report claimed. Julian remembered her body, pale and bloated, washing ashore near Sanibel, her dark hair tangled with seaweed. The coroner, a friend of Richard’s who frequented the estate’s poker nights, ruled it accidental, his signature quick on the death certificate. Julian kept her Kodak Instamatic, its plastic body scratched, and took his first photo after her death: the empty deck, water pooling like blood under the storm’s aftermath.

Richard’s rise was a darker story, one Julian had pieced together over years of overheard conversations and glimpses into locked briefcases. Born in 1940 to Italian immigrants in Tampa, Richard ran numbers for the Trafficante family as a teenager, dodging cops during the Bolita lottery days of the 1950s, when illegal gambling thrived in Ybor City’s cigar factories. By the 1960s, he leveraged mob loans to buy cheap land in Cape Coral, capitalizing on the city’s recovery from the land scams that led to lawsuits and state oversight. His alliance with Santo Trafficante Jr., who ran Florida’s underworld until his death in 1987, gave him muscle—union leaders vanished, competitors’ construction sites burned in suspicious fires. By 1995, Crane Enterprises controlled half of Cape Coral’s new developments, and Richard, eyeing a U.S. Senate run, bankrolled campaigns across Florida, including early support for Jeb Bush’s anticipated 1998 bid. His study was a nerve center, where deals were sealed over bourbon and cigars, and obstacles were “cropped out.”

At 15, Julian witnessed his first kill. Richard’s fixer, Marco—a wiry Sicilian with a scar across his cheek from a knife fight—garroted a rival developer in the estate’s boathouse, the man’s gasps muffled by the lapping water and the hum of a generator. “Document it,” Richard ordered, handing Julian a Polaroid SX-70, its instant film a novelty in 1981. Julian’s hands trembled as he snapped the photo, the image developing before his eyes: the victim’s face frozen, eyes bulging, wire tight around his throat. The thrill hooked him, a rush greater than any drug, a sense of godlike control over life and death.

By 17, Julian claimed his own victim: Carla Diaz, a Miami Herald reporter probing Richard’s 1983 campaign for a state senate seat. Julian lured her to Matlacha Pass for a “sunset shoot,” pushing her from the boat into the choppy waters, her screams swallowed by the Gulf. The police, swayed by a Crane donation to the sheriff’s foundation, ruled it a drowning, no autopsy ordered. Photography became his ritual, each kill a composition—lens as confessional, frame as trophy.

He studied photography at the University of Miami from 1984 to 1988, living in a Coral Gables apartment filled with reggae posters and darkroom equipment. His professor, Dr. Harlan Weiss, a grizzled New Yorker with a passion for street photography, praised his portfolios: “Your work has darkness, Julian. It’s not just technique—it’s a vision.” Julian’s classmates envied his skill but whispered about his aloofness, his late-night absences from dorm parties. One, a drug dealer named Tony, tried blackmailing him over a cocaine deal gone sour in 1987. Julian staged Tony’s overdose in a South Beach alley, photographing the body with a Nikon F3, the needle still in his arm, the neon glow of a club sign casting eerie light.

Now, in the study, Richard handed Julian a dossier on Sam Carver, typed on a typewriter, the paper yellowed from cigarette smoke. “He’s a problem,” Richard said, lighting another cigar. “Vietnam vet, stubborn as hell. Took a bullet in ‘85 busting a Trafficante warehouse in Tampa. He’s got a vendetta against people like us. Find a way to stop him.”

Julian nodded, slipping the dossier into his bag. “I’ll start watching him.”

He drove to his gallery in Cape Coral’s modest arts district, a converted warehouse near Cultural Park Boulevard, its exterior painted coral pink to match the city’s aesthetic. The space was cool, air-conditioned, with exposed brick walls and track lighting illuminating his latest exhibit, Fleeting Shadows. The prints hung in sleek black frames, their subjects—decaying docks, abandoned boats—drawing murmurs from visitors. Detective Sam Carver arrived mid-afternoon, his trench coat out of place in the Florida heat, his limp pronounced from a bullet that shattered his femur a decade earlier in a shootout that left two Trafficante goons dead.

“Nice work, Mr. Crane,” Sam said, his gravelly voice echoing in the quiet gallery. He was 52, broad-shouldered, his face a map of wrinkles from years on the force, his .38 Smith & Wesson Model 10 revolver concealed under his coat. “Know Lena Voss? Witnesses saw her enter your building the night she vanished.”

Julian’s smile was a practiced mask, honed over years of dodging scrutiny. “She interviewed me for a story. Left around ten, excited about her article. Tragic if something happened.”

Sam’s hazel eyes lingered on a print—a woman’s face in shadow, her gaze unnervingly vacant, lips parted as if in a silent scream. He noticed a hair clip on the floor near the baseboard, silver with a pearl inlay, identical to one Lena wore in a photo from her mother’s house. “Mind if I look around?” he asked, his tone deceptively casual.

“Be my guest,” Julian said, but his pulse quickened, a faint tremor in his fingers. As Sam wandered the gallery, pausing at each frame, Julian slipped the clip into his pocket, his mind already planning the next move.

That evening, he drove to a secluded spot near his building, where a fire pit was hidden behind a screen of hibiscus bushes. He burned a batch of test prints—outtakes from Lena’s shoot, too blurry for his standards—watching the flames consume the paper, embers spiraling into the night like fireflies. His pager buzzed, the Motorola’s green display glowing: “Exhibit’s a hit. Dinner tomorrow? – S.” Sarah Kline, his gallery assistant in Miami, a 25-year-old art history graduate from NYU with blonde hair and a laugh that almost made him feel human. He typed a reply: “Can’t wait.”

Chapter 3: The Hunt Begins

Sam Carver’s office at the Cape Coral Police Department was a cramped, windowless box on the second floor, its cinderblock walls yellowed from years of cigarette smoke, though smoking had been banned since 1992. A flickering fluorescent light buzzed overhead, casting harsh shadows on stacks of manila folders, a rotary phone that rang incessantly, and a chipped mug filled with stale coffee. The air smelled of toner from an overworked Xerox machine in the hall, and a small desk fan did little to dispel the humidity seeping through the building’s seams. Sam sat hunched over Lena Voss’s case file, his bad leg propped on a stool, the ache in his femur a constant reminder of the 1985 shootout in Tampa where he took a bullet busting a Trafficante warehouse. At 52, he was a relic of a different era—born in 1943 in Fort Myers, a Vietnam vet who served two tours as a radio operator in Da Nang, dodging mortars and Agent Orange. He joined the police in 1972, rising through the ranks, but his marriage to Ellen crumbled in 1990 under the strain of long hours and his obsession with justice. Their daughter, Emily, 18, was now a freshman at Florida State University, her photo on his desk the only warmth in the room.

Lena’s disappearance was the third case linked to Crane Enterprises. In 1994, an environmentalist named Rachel Gomez vanished after protesting a Crane marina that destroyed mangrove habitats; in 1993, a journalist, Tom Heller, went missing mid-investigation into Crane’s campaign donations. Sam flipped through Lena’s file: her last article, a scathing piece on the Riverfront Marina, mentioned “anonymous sources” and “mob ties.” A Polaroid showed her smiling at a News-Press picnic, her red hair bright, a silver hair clip with a pearl catching the light.

Sam drove his unmarked Ford Crown Victoria to Lena’s family home in Fort Myers, a modest ranch house off McGregor Boulevard, its lawn dotted with hibiscus bushes blooming red. Clara Voss, Lena’s mother, answered the door, her eyes red-rimmed, a tissue crumpled in her hand. “She was onto something big,” Clara said, clutching a photo of Lena in a graduation cap from the University of Florida, class of 1991. “She called me that day, said she was meeting Julian Crane. Thought he was charming but evasive. She was scared but wouldn’t back down.”

Back at the precinct, Sam’s partner, Officer Luis Ruiz, a 30-year-old with a buzz cut and a quick smile, handed him a BellSouth phone log. “Lena called Crane’s studio at 8 p.m.,” Ruiz said, pointing to a highlighted line. “Twenty-minute call, her last.”

Sam decided to tail Julian. In his Crown Vic, no air conditioning, sweat soaked his shirt as he followed Julian’s Mercedes through Cape Coral’s traffic—minivans, pickup trucks towing boats, construction dust clouding the air along Del Prado Boulevard. Julian stopped at a riverfront diner, the Pelican’s Nest, meeting a woman—blonde, mid-20s, laughing as they sat on the patio under string lights. Sam recognized her from gallery ads: Sarah Kline, Julian’s assistant in Miami.

Julian’s romance with Sarah had begun three months earlier at his Design District exhibit. She’d approached him during the opening, her NYU art history degree evident in her questions about his influences. Over crab cakes and key lime pie at a riverfront restaurant, she’d said, “Your photos make me feel the weight of this place—the canals, the decay. It’s like you’re capturing souls.” Julian had laughed, leaning in to kiss her under the string lights. “That’s a bit creepy, Sarah.” But her words fed his ego, her warmth a temporary balm for the coldness within. Now, at the diner, she reached for his hand. “You’ve been distant lately. Everything okay?”

“Work,” he lied, squeezing her fingers, his smile a mask. “Big project coming up.” In his mind, she was a complication—too curious, too close, her questions edging toward danger.

That night, Richard paged Julian from Tallahassee, where he was lobbying for a tax break on his developments. They spoke via a secure landline in Julian’s studio, the river dark outside, a manatee surfacing briefly with a soft splash. “Carver’s asking questions at the precinct,” Richard said, his voice sharp, the static crackling. “He’s got a vendetta from that ‘85 bust. He’s digging into Lena. Handle it.”

Julian nodded, staring out at the water, where the city lights danced like ghosts. “I’ll need a new subject first.”

He’d already chosen: Mark Tate, Richard’s former campaign manager, now hiding in a motel off Pine Island Road with ledgers proving Crane’s mob ties. Mark, 45, was a former Marine who joined the 1992 campaign, loyal until he stumbled on a safe containing evidence of payoffs to Lee County judges and contracts with Trafficante front companies. He’d fled, paranoid, after a near-miss with a hitman. Julian drove to a payphone near a 7-Eleven, the neon sign flickering, and called Mark as “Ethan Black, photojournalist.” “I hear you’ve got a story,” he said, voice low, the receiver warm from his grip. “I can get it out there.”

Mark, his voice trembling, agreed to meet at a diner in North Fort Myers tomorrow. “Be discreet,” he said. Julian hung up, smiling. The frame was set.

Chapter 4: Depth of Field

The diner, a greasy spoon called The Crab Shack, smelled of fried fish and hush puppies, its jukebox blaring Merle Haggard’s “Okie from Muskogee” over the clatter of plates and the hum of ceiling fans. Julian, disguised with a fake mustache and wire-rimmed glasses, slid into a red vinyl booth across from Mark Tate. The 45-year-old was gaunt, his Marine buzz cut graying at the temples, his eyes darting to the door every few seconds, a habit from years of vigilance. Once Richard’s right-hand man during the 1992 campaign, Mark had turned whistleblower after finding a locked safe in Crane Enterprises’ Fort Myers office. Inside were ledgers detailing payoffs to county judges, invoices for “consulting” fees to Trafficante front companies, and audio cassettes of Richard negotiating with mob bosses. Mark’s hands shook as he clutched a Styrofoam coffee cup, the diner’s fluorescent lights casting harsh shadows on his face.

“I know what they’re doing,” Mark whispered, leaning forward, his voice barely audible over the jukebox. “Crane’s tied to murders, land grabs, the whole marina deal. I’ve got proof—recordings, documents. They’ll kill me if they find me.”

Julian, posing as Ethan Black, leaned forward, his Nikon FM2—a rugged, manual camera—resting on the table as a prop for authenticity. “That’s big,” he said, his tone sympathetic, eyes locked on Mark’s. “A story like that needs visuals. Let’s do a shoot at your motel, tomorrow night. Somewhere safe.”

Mark hesitated, his fingers tightening on the cup, coffee sloshing. “Room 12, Sunset Inn, off Pine Island Road. 10 p.m. Nobody else.”

Julian nodded, his smile reassuring. “I’ll be there.”

He spent the day preparing with meticulous care. In his darkroom, he loaded a fresh roll of Ilford Delta 3200, a high-speed film perfect for the motel’s dim light, its grain adding a gritty texture he loved. He cleaned his silenced .22 Walther PPK, a compact pistol favored by mob hitmen for its quiet efficiency, its weight familiar in his hand. He tested his lighting setup—portable battery-powered strobes, collapsible for transport, to mimic moonlight through cheap motel blinds. In a locked case, he packed a small bottle of chloroform as a backup, its sweet smell a precaution he rarely needed.

At 10 p.m., he knocked on the door of Room 12 at the Sunset Inn, a rundown motel with faded flamingo wallpaper and a neon vacancy sign that flickered like a dying pulse. The room reeked of cigarette smoke, stale beer, and Mark’s sweat-soaked fear. A single lamp cast a yellow glow, the bed unmade, a duffel bag stuffed with documents on the floor. Mark let him in, his eyes bloodshot. “You sure this’ll help?” he asked, clutching a folder of papers—photocopies of the ledgers, a cassette tape labeled “RC Meeting 3/94.”

“Trust me,” Julian said, setting up a light stand, the strobe’s hum blending with the buzz of a faulty air conditioner. He positioned Mark near the window, the blinds slatted to let in slivers of moonlight. “Hold the folder, like you’re showing the evidence.” As Mark complied, Julian drew the Walther from his camera bag, the silencer gleaming. The shot was a muffled pop, like a champagne cork, and Mark slumped to the floor, blood pooling on the linoleum, a crimson stain spreading like ink.

Julian worked quickly, arranging the body: Mark’s hand clutching the folder, head tilted toward the window, the blinds casting dramatic chiaroscuro across his face. He shot 24 frames, the camera’s shutter a rhythmic chant—close-ups of the wound, wide shots of the room’s squalor, the interplay of light and shadow a perfect composition. He titled the series Vanishing Truth in his mind, destined for a Cuban art collector in Miami who paid $750,000 for such “unique” works at a clandestine auction.

He gathered the documents and cassette, stuffing them into a garbage bag, and drove to a dumpster behind a closed strip mall, where he burned them, the flames licking the night air, the acrid smoke blending with the scent of nearby mangroves. Back in his studio, he developed the prints, the images emerging under the red safelight, Mark’s lifeless eyes staring back, a masterpiece of control.

Sam Carver, meanwhile, hit a breakthrough. At the precinct, Ruiz handed him a BellSouth phone log, the paper crinkled from handling. “Lena called Crane’s studio at 8 p.m.,” Ruiz said, pointing to a highlighted line. “Twenty-minute call, her last.” Sam drove to the News-Press office on Fowler Street, a low brick building with a sign faded from years of sun. Lena’s editor, Marjorie Wells, a gruff woman in her 50s with a chain-smoker’s rasp, tapped a pencil on her desk. “Lena said Julian was evasive but knew more than he let on,” she said. “She was scared but determined to get the story.”

Sam tailed Julian in his Crown Vic, the car’s lack of air conditioning leaving him drenched in sweat as he navigated Cape Coral’s traffic—minivans, pickup trucks towing boats, construction dust clouding the air along Del Prado Boulevard. He followed Julian to the Sunset Inn, arriving too late; the room was cleaned, Mark gone. But a maid, a middle-aged woman with tired eyes, mentioned a “photographer guy” leaving with a tripod. “Had a fancy camera,” she said, chewing gum.

Richard met with Angelo Trafficante, the current head of the family’s remnants, in a smoky cigar bar in Tampa’s Ybor City. The air was thick with Latin jazz from a jukebox, the walls lined with sepia photos of cigar rollers from the 1920s. Angelo, 60, with a pockmarked face and a gold pinky ring, sipped rum. “Your son’s sloppy,” he said, exhaling smoke. “This detective—Carver—he’s trouble. Clean it up, or we will.”

“Julian’ll fix it,” Richard said, his voice tight, but doubt crept in, a crack in his usual confidence.

Chapter 5: Focal Point

Julian’s obsession with Sam Carver grew into a consuming fire. He spent days researching, driving to Sam’s modest apartment off Santa Barbara Boulevard, a one-bedroom unit in a stucco complex with peeling paint and a communal pool clouded with algae. Using a Nikon F3 with a 200mm telephoto lens, he photographed Sam from a rented van parked across the street—Sam eating a grouper sandwich at a diner, the grease glistening on his fingers; talking to his ex-wife Ellen on a payphone outside a Winn-Dixie, his shoulders slumped; driving to Tallahassee to visit Emily at FSU, his Crown Vic weaving through weekend traffic. The photos, grainy and candid, filled a secret album in Julian’s darkroom, locked behind a false panel, each image a study in vulnerability.

Sam’s life unfolded in Julian’s viewfinder. Born in 1943 in Fort Myers, Sam joined the Marines in 1968, serving two tours in Vietnam, his radio crackling with orders under mortar fire. Back home, he became a cop in 1972, his idealism eroded by the corruption he saw—sheriffs taking bribes, developers like Richard skating free. His marriage to Ellen, a schoolteacher, ended in 1990, the stress of his job and a miscarriage driving a wedge. Emily, their only child, was his anchor, her college acceptance a rare point of pride.

Sarah Kline, Julian’s lover, noticed his distraction. Their romance, sparked three months earlier at his Miami exhibit, had been a whirlwind—nights in her Coconut Grove apartment, days wandering art fairs. She was 25, with blonde hair and a laugh that cut through his darkness. They spent a weekend in Key West, staying at a pastel-colored inn near Duval Street, visiting the Hemingway House, where cats roamed the gardens. Over conch fritters at a dockside bar, she pushed: “You’re somewhere else, Julian. What’s going on?”

He brushed it off, kissing her under a banyan tree, its roots twisting like his thoughts. “Just work,” he said, his smile forced. But later, photographing a drowned seagull on the beach, its feathers matted with sand, he saw Sarah watching, her expression uneasy. Back in Cape Coral, she found a stray negative in his studio, slipped under a light table—a blurred image of a woman’s face, eyes vacant, lips parted. “What is this?” she demanded, holding it to the light.

“A test shot,” he lied, snatching it, his voice sharp. “Old project.” Her suspicion lingered, a crack in their bond, her eyes searching his for truths he’d never share.

Richard called, his voice urgent over the landline from Tallahassee, where he was meeting legislators. “Carver’s poking into the motel,” he said, the static crackling. “He’s got the maid’s statement. End him, now.”

Julian planned the trap: a “charity photoshoot” at an abandoned boatyard near Matlacha, its docks rotting into the Gulf, tangled with mangrove roots and barnacles. He spent a day rigging the pilings with loosened supports, testing their give with a crowbar, ensuring a collapse that would look accidental—a dock giving way under weight, a tragic fall into shallow water. He sent Sam an anonymous note, typed on a Brother typewriter: “Charity shoot, Matlacha boatyard, midnight, July 15. Exclusive access.”

Chapter 6: Exposure

The boatyard at midnight was a symphony of decay: waves lapping against rotting pilings, the creak of weathered wood, the buzz of mosquitoes drawn to the brackish water. The air smelled of fish and salt, the mangroves casting jagged shadows under a half-moon. Julian waited in the shadows, his Canon EOS-1 on a tripod, a strobe light ready to blind. His Walther PPK was tucked in his jacket, the scalpel a backup in his boot.

Sam Carver arrived, his trench coat hiding a Kevlar vest and his .38 Smith & Wesson revolver, his limp pronounced on the uneven ground. The boatyard was eerie, the hulks of abandoned shrimp boats looming like ghosts. “What is this, Crane?” Sam asked, his voice low, hand resting near his holster.

“A shoot,” Julian said, his smile predatory. “You’re the star, Detective.” He triggered the strobe, the blinding flashes disorienting Sam, who squinted, raising a hand. Julian lunged with the scalpel, its blade glinting, aiming for Sam’s throat.

Sam, instincts honed by years on the streets, dodged, his fist cracking against Julian’s jaw, a crunch of bone. They grappled on the dock, the wood groaning under their weight. Julian aimed a kick at Sam’s bad leg, but Sam swung a rusted chain from a piling, slamming Julian against a support beam. The rigged pilings gave way, collapsing in a thunder of splintered wood, plunging both men into the shallow, murky water. Sam scrambled out, coughing, his lungs burning with salt and mud, as Julian floundered, his jacket caught on a jagged board.

Two squad cars screeched into the boatyard, their sirens piercing the night, flashlights slicing through the dark. Officer Ruiz, leading the backup Sam had secretly called, hauled Julian from the water, cuffs snapping onto his wrists, the cold steel biting into his skin. Julian, soaked and bruised, laughed maniacally, blood trickling from his split lip. “You think you’ve won?” he spat. “The Cranes own this coast.”

At the precinct, in a stark interrogation room with a one-way mirror, Julian sat chained to a table, his suit ruined, his smirk defiant. Sam leaned across, his voice steady. “We found your darkroom, Crane. Photos, chemicals, everything. You’re done.”

“It’s art,” Julian said, leaning back. “You wouldn’t understand.”

Part II: The Negative

Chapter 7: Trial by Fire

The Lee County Courthouse in Fort Myers stood as a monolithic slab of concrete and glass, its modern facade a sharp contrast to the historic charm of downtown Fort Myers, where palm trees lined Edison Avenue and the scent of blooming jacaranda mingled with the exhaust of passing cars. Built in the late 1980s, the courthouse was a hub of justice—or, for some, a stage for its subversion—in Southwest Florida, handling cases from petty theft to high-profile murders. In September 1995, as Hurricane Opal churned in the Gulf, threatening to make landfall, the building became the epicenter of the trial of Julian Crane, a spectacle that drew media from Miami, Tampa, and even national outlets like CNN. News vans lined the streets, their satellite dishes piercing the sky, while reporters in linen blazers jostled for soundbites, their cameras flashing like Julian’s own strobes.

Inside, Courtroom 3A was a pressure cooker, the air conditioning struggling against the humidity seeping through the double doors, creating a chill that did little to cool the tension. The room was paneled in dark oak, its high ceiling adorned with lazily whirring fans that stirred papers on the attorneys’ tables. Rows of benches were packed with spectators: grieving families of victims clutching tissues, art enthusiasts whispering about the “killer photographer,” local politicians gauging the fallout for Richard Crane’s empire, and reporters scribbling furiously on legal pads, their pencils scratching like insects. Judge Maria Alvarez, 62, presided from her elevated bench, her salt-and-pepper hair pulled into a tight bun, her black robes flowing like a shadow. A Latina judge with 20 years on the bench, she had a reputation for unyielding fairness, having sentenced mobsters, corrupt councilmen, and drug lords with equal severity. Her gavels, custom-made from mahogany, cracked like thunder, silencing the room.

Julian sat at the defense table, flanked by his legal team, his appearance meticulously curated despite his circumstances. He wore a tailored linen suit in ivory, the fabric light against the Florida heat, his face a mask of stoic composure, though his blue eyes darted to the gallery, framing the scene as if through a viewfinder. His hands, uncuffed for the trial but scarred from the boatyard fight, rested on the table, fingers twitching as if longing for a shutter release. To his left was Cassandra Wells, his lead attorney, a sharp-featured woman in her mid-40s from Miami, known for defending high-profile clients with ties to organized crime. Her navy power suit was crisp, her briefcase stuffed with motions, appeals, and forensic reports, her sharp mind honed by years of outmaneuvering prosecutors. Flanking her were two associates, young lawyers fresh from UF Law, their briefcases open, papers spilling onto the table.

Across the aisle, Assistant U.S. Attorney Marcus Hale paced like a caged panther, his wiry frame taut with energy. Hale, 42, with a bald head that gleamed under the courtroom lights and a voice that carried like a preacher’s, had built his career dismantling crime networks—from Miami drug cartels to Tampa’s white-collar schemes. This case was personal; a college friend, a journalist, had been killed in a 1987 Trafficante hit, and Hale saw the Cranes as extensions of that rot. His table was piled with evidence boxes: leather-bound photo albums from Julian’s darkroom, forensic reports typed on dot-matrix printers, witness statements scrawled in blue ink.

The trial, now in its third week, had reached a critical juncture. Today, the prosecution called its key witnesses, and the courtroom buzzed with anticipation, the air thick with the scent of coffee from a thermos passed among reporters. The bailiff, a burly man with a handlebar mustache named Frank, called the court to order, his voice booming: “All rise!” Alvarez entered, her robes rustling, and the room settled into a tense silence.

Marcus Hale stood, adjusting his tie, and called Detective Sam Carver to the stand. Sam shuffled forward, his limp more pronounced under the stress, his ill-fitting suit—a navy blazer bought at Sears—wrinkled from a night of reviewing case files. He swore the oath, his hand on a worn Bible, and sat, his hazel eyes scanning the room, lingering on Julian. Hale approached, his voice steady but forceful. “Detective Carver, please describe the events at the Matlacha boatyard on July 15, 1995.”

Sam leaned into the microphone, its feedback squealing briefly before stabilizing, his gravelly voice filling the room. “I got an anonymous note—typed, no signature—about a ‘charity photoshoot’ at the boatyard. Smelled like a trap, so I called backup, kept ‘em out of sight. Got there at midnight, found Crane with a camera, strobe light ready. He flashed it to blind me, then came at me with a scalpel, said I was ‘just another exposure.’ We fought on the dock; he’d rigged it to collapse. I tackled him, the pilings gave way, we hit the water. Backup pulled us out, cuffed him.”

The gallery murmured, a ripple of whispers like waves on a canal. Cassandra Wells shot to her feet, her voice sharp. “Objection, Your Honor! The anonymous note is hearsay, and the detective’s account lacks corroboration.”

Alvarez’s gavel cracked, silencing the room. “Overruled. The note’s context is admissible, and backup officers will corroborate. Proceed, Mr. Hale.”

Hale nodded, his eyes gleaming. “Detective, tell us about the darkroom raid.”

Sam adjusted his posture, wincing as his leg ached. “We got a warrant for a boatyard warehouse Crane used. Found a darkroom—portable enlarger, chemical trays, albums. Hundreds of photos: Lena Voss, Mark Tate, others, all dead, posed like art pieces. Developer residue matched fibers from the motel where Tate was killed. Metadata from the negatives—early tech, but solid—linked to disappearance dates.”

The gallery erupted in gasps, a mother in the front row—Clara Voss—sobbing into her hands. Wells objected again: “Speculative! Metadata analysis in 1995 is unreliable!” Alvarez overruled, her expression stern.

Richard Crane watched from the back row, his silver hair disheveled, his linen suit creased from sleepless nights in Tallahassee. His desperation to save Julian had consumed him since the arrest. From his gubernatorial mansion, he’d funneled millions through shell companies—Crane Holdings, Gulf Ventures—to fund the defense, hiring private investigators to dig dirt on jurors. One, a high school teacher named Linda Perez, had a gambling debt; another, a mechanic named Roy, had a DWI swept under the rug by a Crane-friendly cop. Richard had called in favors from Trafficante contacts, orchestrating threats against a key witness—the motel clerk who saw Julian with Mark. The clerk, Maria Lopez, vanished for a week, later found hiding in Naples, her family threatened by anonymous calls traced to a payphone in Tampa.

In a jail visit the previous week at the Lee County Detention Center, Richard had pressed his palm against the scratched plexiglass, his voice hoarse from chain-smoking. “Cassandra’s filing motions to suppress the photos,” he whispered, his eyes bloodshot. “I’ve got judges in my pocket—Judge Harlan owes me from ‘92. Appeals are lined up. Hang in there, son.”

Julian had nodded, his eyes cold as steel. “They don’t see the art, Dad. It’s all frames to me. Every moment, captured.”

The prosecution’s next witness was Sarah Kline, Julian’s former lover. She took the stand, her blonde hair pulled back in a tight ponytail, her hands trembling as she clutched a tissue, her eyes avoiding Julian’s. Hale approached gently, his voice softer. “Ms. Kline, please describe what you found in Mr. Crane’s studio.”

Sarah’s voice broke, barely audible. “A negative, under his light table. A woman’s face—eyes vacant, lips parted, like she was dead. I thought it was a mistake, a test shot. But after his arrest, I saw Lena Voss’s photo in the paper. It was her.”

The courtroom fell silent, the only sound the hum of the fans. Hale held up the negative, encased in a plastic evidence bag, its ghostly image visible under the lights. “Is this the negative?” he asked.

“Yes,” Sarah whispered, tears spilling. “I gave it to the police.”

Wells cross-examined with icy precision, her heels clicking on the hardwood floor. “Ms. Kline, you were intimate with my client for months. Were you jealous, perhaps? Looking for reasons to hurt him?”

Sarah shook her head, her voice firming. “I loved him. But those photos… they weren’t art. They were confessions.” The gallery buzzed, reporters scribbling furiously.

The evidence presentation was relentless. Hale unveiled the darkroom albums, projecting images on a courtroom screen mounted on a tripod. Lena Voss appeared first, her body posed on the chaise, hair fanned, eyes glassy, the river’s reflection a haunting backdrop. Gasps rippled through the room, Clara Voss collapsing into her husband’s arms. Mark Tate’s image followed, his hand clutching a ledger, moonlight casting slatted shadows through motel blinds. Other victims—Rachel Gomez, Tom Heller, a half-dozen more from Julian’s early years—filled the screen, each a meticulously staged tableau of death.

Forensic experts took the stand, their reports printed on dot-matrix paper. Dr. Emily Chen, a chemist from the FDLE lab, testified: “The developer residue in the albums matches carpet fibers from the Sunset Inn, where Mark Tate was killed. Traces of midazolam were found in Voss’s toxicology, consistent with sedation.” A digital analyst, using 1995’s rudimentary metadata tools, confirmed: “Timestamps on the negatives align with disappearance dates—Voss on June 10, Tate on July 5.”

Richard’s efforts to save Julian intensified outside the courtroom. From his Tallahassee office, he made frantic calls on a secure line, his Rolodex spinning. He contacted Judge Harlan, who’d received Crane campaign funds in ‘92, hinting at a “favor” for a mistrial. He bribed a juror, Linda Perez, offering to clear her $20,000 casino debt through a shell company, but the FBI, tipped by Sam’s suspicions, intercepted the deal, wiring the intermediary. Richard orchestrated a media campaign, giving tearful interviews to WBBH-TV in Fort Myers: “My son’s a genius, targeted by my political enemies,” he said, clutching a childhood photo of Julian, his eyes glistening for the cameras. He even pressured a state senator, a Crane ally, to push for a mistrial, citing “biased media coverage,” but Alvarez rejected the motion, her gavel a sharp rebuke.

The prosecution called Clara Voss, Lena’s mother, as an emotional closer. She took the stand, a frail woman in her 50s, her graying hair pinned back, her hands clutching a rosary. “My daughter sought truth,” she said, her voice steady despite tears. “She wanted to save this city from greed. Julian Crane stole that from her, from us.” The jury, a mix of locals—two teachers, a fisherman, a nurse, a mechanic, a retiree—shifted uncomfortably, some wiping their eyes.

The defense’s turn was a desperate gambit. Wells called a psychologist, Dr. Alan Roth, who argued Julian suffered from “artistic dissociation,” a fabricated condition suggesting he blurred reality and art. “His photographs were expressions, not confessions,” Roth said, adjusting his glasses. Wells argued the photos were planted, the metadata unreliable, but her motions to suppress the evidence were denied, Alvarez citing “overwhelming corroboration.”

A bombshell came mid-trial: Maria Lopez, the motel clerk, reappeared after FBI protection. She testified, her voice trembling: “I saw Mr. Crane leave Room 12 with a tripod, the night Tate disappeared. Then someone called my house, said my kids would suffer if I talked.” The jury gasped, and Richard, in the gallery, paled, his hands clenching.

Closing arguments were electric. Hale stood before the jury, his voice rising: “Julian Crane didn’t just kill—he framed death as art, turning lives into trophies. Lena Voss, Mark Tate, and others deserved better. Justice sees through his lens.” Wells countered, her tone icy: “This is a witch hunt, targeting a brilliant artist because of his father’s enemies. The evidence is circumstantial, the photos ambiguous.”

The jury deliberated for three days, the courthouse tense, rain from Opal’s fringes pounding the windows, the air heavy with the scent of wet asphalt. On September 28, 1995, they returned: guilty on all counts—first-degree murder, kidnapping, evidence tampering. Julian’s face remained blank, his eyes fixed on the ceiling, as if imagining one last frame. Richard slumped in his seat, his empire cracking, his hands shaking as he lit another cigar outside, the smoke lost in the rain.

Chapter 8: Shutter Close

The sentencing hearing, two weeks later, was a somber affair, the courtroom half-empty as the media frenzy waned, reporters chasing Opal’s landfall in Pensacola. Judge Alvarez, her expression unreadable, listened as Marcus Hale requested life without parole, citing the “heinous, premeditated nature” of Julian’s crimes. Cassandra Wells argued for leniency, claiming Julian’s “psychological condition” warranted a chance at rehabilitation, but her words rang hollow, the jury’s verdict unyielding.

Julian stood as Alvarez delivered the sentence, her voice cutting through the room like a blade. “Julian Crane, for the murders of Lena Voss, Mark Tate, and others, you are sentenced to life imprisonment without the possibility of parole at Florida State Prison.” The gavel cracked, final as a shutter closing. Julian’s eyes flickered, a faint smile tugging at his lips, as if he saw the moment as a perfect composition—himself, framed by justice.

He was transferred to Florida State Prison, a stark complex in the Panhandle’s pine forests, its gray walls and razor wire a far cry from Cape Coral’s sunny canals. In his cell, a 6-by-8-foot concrete box with a steel bunk and a single barred window, Julian was stripped of his camera, his suits replaced by an orange jumpsuit. But his mind remained a darkroom, conjuring images of his kills. He scratched compositions into the walls with a smuggled nail, crude sketches of Lena’s chaise, Mark’s motel room, the boatyard’s collapse. The guards, noticing, confiscated the nail, but Julian’s fingers traced the air, framing invisible scenes, his obsession unquelled.

Richard Crane’s downfall was swift and brutal. The trial exposed his complicity: phone logs showed calls to Julian post-kills, bank records traced payments to cover-ups, and Mark Tate’s cassette—recovered from the dumpster ashes—captured Richard ordering “problems handled.” Subpoenas from the U.S. Attorney’s Office unraveled Crane Enterprises, revealing a web of shell companies and mob ties. Richard resigned his unofficial “advisor” role in Tallahassee, his Senate dreams shattered. In November 1995, he was indicted on RICO charges, accused of racketeering with the Trafficante family. Awaiting trial in a Miami detention center, he attempted suicide, swallowing a handful of Valium stolen from a guard, but survived, waking in a hospital bed, his wrists cuffed, his legacy reduced to tabloid headlines: “Crane Empire Falls: Father-Son Killing Duo Exposed.”

In a final jail visit before his transfer, Richard faced Julian through the plexiglass, his face gaunt, his eyes hollow. “You failed me,” Richard hissed, his voice barely audible. “I gave you everything.”

Julian leaned forward, his smile cold. “You gave me the frame, Dad. I filled it.”

Sam Carver retired three months after the verdict, the case’s toll etching deeper lines into his weathered face. He moved to a modest bungalow on Sanibel Island, its porch overlooking the Gulf, where he fished for redfish and tarpon, the waves a soothing rhythm. But nightmares persisted—Lena’s glassy eyes, Mark’s bloodied hand, the faces from Julian’s albums invading his sleep like overexposed negatives. He kept Emily’s photo on his nightstand, calling her weekly, her voice a lifeline. “I’m proud of you, Dad,” she’d say, but Sam felt hollow, the cost of justice too steep.

Sarah Kline, heartbroken but resolute, left Miami to open a small gallery in Cape Coral’s arts district, a storefront near the library with white walls and soft lighting. She displayed Julian’s “safe” works—canal sunsets, abandoned boats, the eerie beauty of mangrove shadows—donated anonymously by a collector who’d bought them before the trial. Patrons praised their “dark energy,” whispering theories about the artist’s tormented soul, unaware of the abyss from which they sprang. Sarah, curating the exhibit, avoided those prints, her hands trembling as she hung them, the memory of Julian’s touch a ghost she couldn’t shake.

In a quiet moment, as rain pattered on the gallery’s roof, Sarah stood before a photo of a Caloosahatchee sunrise, its light fracturing through storm clouds. She wondered if Julian had seen beauty or only control in that moment. She’d never know, and that uncertainty was her punishment.

Cape Coral moved on, its canals gleaming under the Florida sun, new condos rising where mangroves once stood. The marina opened in 1996, a gleaming monument to Richard’s vision, but his name was scrubbed from the plaques, the project rebranded by a new developer. The city’s shadows remained, hidden in plain sight, waiting for another lens to expose them.

-The End-

If you liked this book, please consider checking out my other works…